Difference between revisions of "Spontaneous Parametric Downconversion"

(→Quantum Eraser) |

(→Overview) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Overview == | == Overview == | ||

| − | Spontaneous parametric downconversion (SPDC) is a non-linear optical process that takes place with the assistance of specially-engineered optical crystals. These optical crystals are designed with specific index of refraction properties along given crystalline axis. When light of a specific frequency is incident upon the lattice, it will | + | Spontaneous parametric downconversion (SPDC) is a non-linear optical process that takes place with the assistance of specially-engineered optical crystals. These optical crystals are designed with specific index of refraction properties along given crystalline axis. When light of a specific frequency is incident upon the lattice, it will undergo a parametric downconversion process. This will result in an overall "splitting" of one incident light beam into two beams, a "signal" and an "idler" beam, at some well-defined angle with respect to the optical input axis (serving as the zero). The quanta of light will experience a downconversion but within this the momentum and energy of the beam is conserved in the signal and idler beams. See figure 1 for an illustration, below for a simplified explanation, and the WikiPedia article for maximum detail.[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spontaneous_parametric_down-conversion]. |

Revision as of 12:45, 20 July 2015

Contents

Quantum Optics and Spontaneous Parametric Downconversion

The goal of this project is to use a series of table-top laser-based optics experiments to investigate various quantum mechanical phenomena. These include, but are not limited to: quantization of the electric field (proof of the existence of photons), single-photon interference, violation of Bell inequalities, and quantum information measurements.

Physics Background

Overview

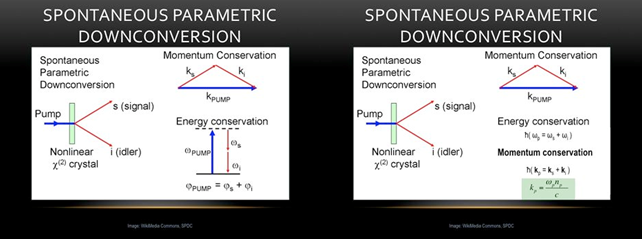

Spontaneous parametric downconversion (SPDC) is a non-linear optical process that takes place with the assistance of specially-engineered optical crystals. These optical crystals are designed with specific index of refraction properties along given crystalline axis. When light of a specific frequency is incident upon the lattice, it will undergo a parametric downconversion process. This will result in an overall "splitting" of one incident light beam into two beams, a "signal" and an "idler" beam, at some well-defined angle with respect to the optical input axis (serving as the zero). The quanta of light will experience a downconversion but within this the momentum and energy of the beam is conserved in the signal and idler beams. See figure 1 for an illustration, below for a simplified explanation, and the WikiPedia article for maximum detail.[1].

Downconversion

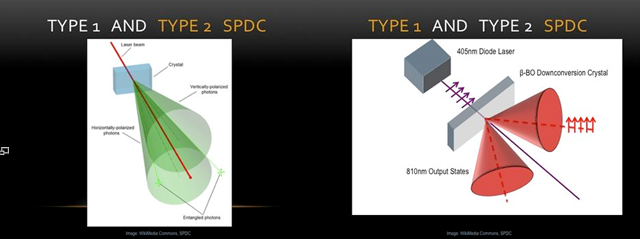

If we reduce the incident beam to a series of single photons, whose existence is a central postulate of quantum theory, the above description need only be slightly altered. A single photon incident on the crystalline lattice has a certain probability of being downconverted via the interaction with the lattice (roughly 1 in 10^12)[2]. When this conversion takes place, the single photon, with its inherent polarization properties, is converted into a pair of polarization entangled photons at half the energy and wavelength. The output pair has the same polarization, but is polarized orthogonal to the input beam. Type II follows the same characteristic downconversion (DC) as the Type I but with one very crucial difference. In Type II downconversion the polarizations of the output beams are now orthogonal to one another (with some overlap in their respective electric fields so that there is a possibility for photon interaction, and unlike that of Type I where there is no possibility for interaction after the downconversion crystal). The way one sets their experiment for Type I or Type II downconversion is by choosing the correct the crystal lattice cut (i.e. purchasing the correct crystal). The lattice will be cut in such a way that the axis with varying indices of refraction will favor one DC type over the other.

Single Photon Fields and g2

NOTE: This section heavily references from Mark Beck's text Quantum Mechanics: Theory and Experiment which is mentioned in the references and available in the lab.

In any optics experiment the experimenters usually convert light to electric current via some photodetector and diode scheme. If one wishes to measure single photons, the question must then arise - how could you distinguish the "granularity" of a single photon incident on your detector from that of the single electrons flowing in your electrical detection scheme? Fortunately there exists a way to quantize the electric field incident on the detector that circumvents this issue entirely. The quantization of the electric field will not be presented in detail here, nor will the derivation of the g2 values. These details can be found in section 16 of Beck.

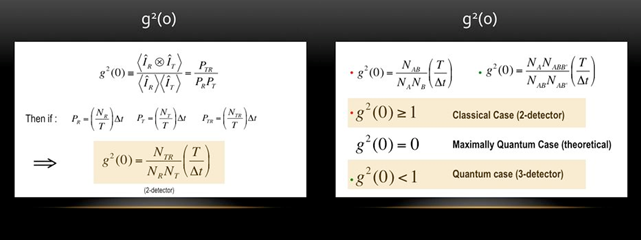

For ease of presentation, it should suffice to say that the g2 factor (degree of second-order coherence) is a numerical value describing the ratio of intensities between two electric fields. This ratio can be cleverly mainpulated, after the coherent electric field from a laser source has been properly quantized, to yield detection probabilities in different regions of space. These probabilities can then be averaged over time to yield estimates for the number of photons one would expect to be incident upon a detector placed in the region of the field. Below are the most basic depictions of these values. For more detail, see the WikiPedia page [3] .

Measurement of photon counts over time at an array of photodetectors can be analyzed for their degree of correlation. Positive, zero, and anti-correlations at the detectors all play a very important role in claiming the nature of the electric field present in the chosen experiment. The constraints on g2 being 0 < g2 ≤ 1 for a quantum mechanical field and g2 ≥ 1 for a classical electric field are determined by analyzing the ratios for the 2-detector and 3-detector schemes for our chosen experiments. To understand this in the context of the experiment, please see the results section.

Double Slit and the Quantum Eraser

Experimental Setup

Basic Setup

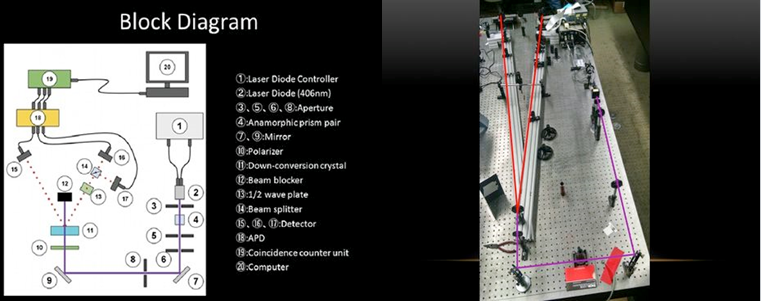

In our experiment we start with a 405nm blue diode pump laser. We then put the laser through an iris and a linear polarizer to ensure horizontal polarization. Once through the polarizer the laser was then pushed through a half wave plate in order to change the polarization of the beam to vertical. After being reflected off of two mirrors the light is incident on the downconversion crystal, producing two 810nm horizontally polarized output beams (signal and idler). A beam blocker was placed down the beam path to block any stray 405nm light. The two output beams travel at an angle of roughly 3 degrees off axis with respect to the input beam. The signal and idler beams travel down their respective legs and reach a photodetector to record both their individual and coincidence counts. Coincidence at the B and B' detectors is determined via a polarizing beam-splitting cube (PBSC) designed for 810nm light. The photodetectors are multi-mode fiber-coupled to a FPGA board and the outputs are sent to a custom LabView counting program (Coincidence.vi or Angle Scan.vi) on a desktop computer setup right on the optics table.

Quantum Eraser Setup

We continued to use the basic setup described above, ensuring that we used a double layered BBO that produces entangled photons. Note that a single layered BBO does not produce entanglement, which is required for the quantum eraser experiment. Down the signal leg, between the downconversion crystal and the PBSC, we installed our interferometer, which included in order, a half-wave plate set to 22.5 degrees, a beam displacement prism (BDP), a half-wave plate set to 45 degrees, another BDP, oriented oppositely in order to recombine the light beams, and finally another half-wave plate set to either 22.5 or zero degrees, depending on the stage of the experiment.

We followed the procedure described in Beck's book to install and align the interferometer. One important note is to calibrate and set all of the wave plates independently of this installation. The fast axes are not always truly aligned how they are marked, and their alignment must be empirically and accurately determined before their use in the interferometer.

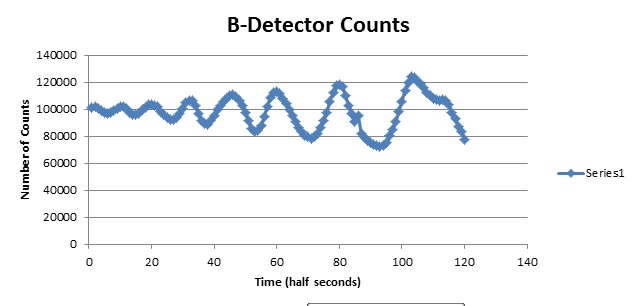

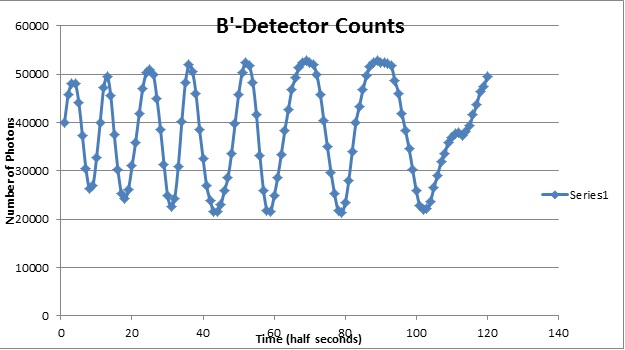

After the interferometer was properly aligned, we verified that it produced interference by setting the third waveplate to our empirically found 22.5 degrees and scanning the path lengths with the picomotor, plotting coincidence counts as a function of time. Proper interference was observed when we saw coincidence counts between AB and AB' oscilate in opposition of each other.

We were not able to complete the rest of the quantum eraser experiment for various reasons, but our suggested procedure is as follows: Set the third waveplate to zero degrees instead of 22.5. This should provide "which-path" information and interrupt the interference pattern. Then insert a quarter-wave plate into the idler leg. Entanglement should ensure that the "which-path" information is erased, and the interference pattern should reappear.

Results

Group 3: Kevin Masson and Alex Schachtner

Maximizing Photon Counts

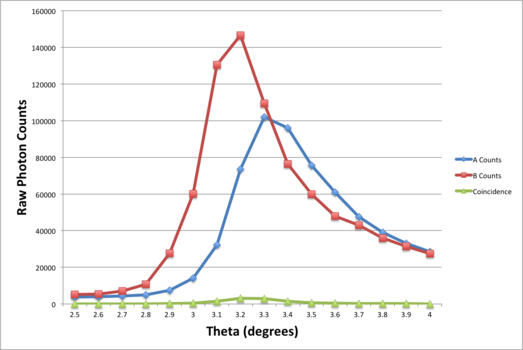

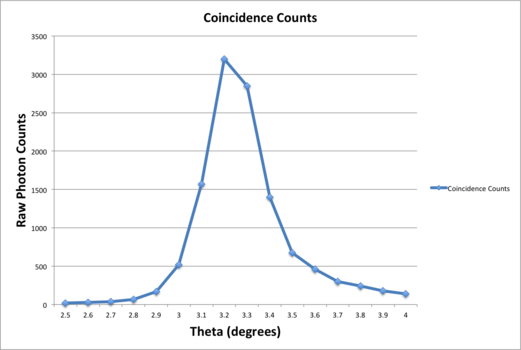

In order to have the best possible experimental results, we sought to maximize the photon counts on each optical leg of the experiment. To do this, we varied the angle of each optical leg from 2.5 degrees to 4 degrees by increments of one-tenth of a degree from the central axis. Recorded values of photon counts are shown below. We found that the maximum counts occurred at approximately 3.2 degrees. This matches the theoretical maximum angle for photon counts of 3 degrees.

Proving the Existence of Individual Photons

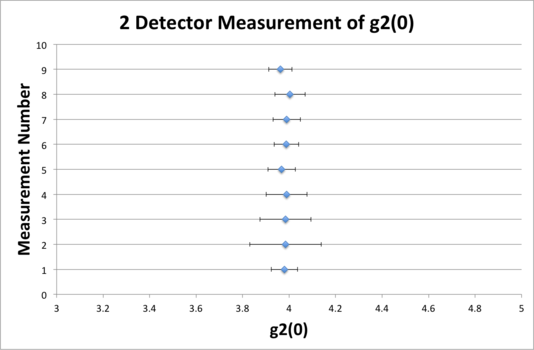

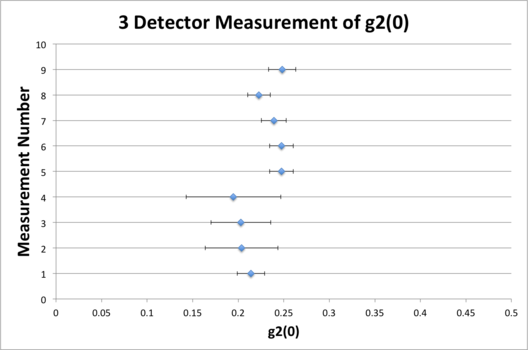

Measurement of individual photons is done in this experiment via determining the g2 value referenced in the background section. Two measurements were devised for comparison of their resultant values - a two-detector measurement for illustrating the classical electric field value of g2, and a three-detector measurement for verifying the quantized electromagnetic field.

For a two-detector scheme, coincidence counts are seen as a result of positively-correlated or non-correlated measurements of a single input electric field being split by the polarizing beam-splitting cube (PBSC). If one pictures the electric field incidence on a refractive crystal, they expect the outputs at subsequent faces to be phase-shifted copies of the input field. This is purely a classical electrodynamic effect - polarized EM plane waves incident on the PBSC become phase-shifted polarized plane waves when re-emitted. g2 measurements at the B and B' detector show these results by expecting g2 ≥ 1 in the mathematical scheme outlined above. Our results indeed show g2 approximately 3.9 for this measurement:

For a three-detector scheme, coincidence counts are a result of anti-correlated measurements on a single-photon field across detectors A, B, and B'. Single photons incident on the PBSC have a 50% probability of reflection or transmission at the PBSC refraction face. When analyzing the AB and AB' coincidence counts, one would expect at least one of these values to be exactly zero when considering a perfect single photon source - the photon will only be incident on either the B or B' detector, not both. Since this is not achievable in the lab, the value can approach zero but will never reach it. However, it should never breach 1 for a quantum mechanical effect to be claim. Our scheme then yields a measurable value of 0 < g2 ≤ 1 by virtue of the ratios outlined above. Our results show an average value of g2 approximately 0.235:

For the next part of our experiment we added the third detector (B') and the polarizing beam splitting cube as described above. In this part we did a coincidence count between sensor A from the signal beam and sensor B from the idler beam from here we then were able record the g2 number for the two detector case. In this case we got a number greater than one which then solidifies the fact of light having a classical characteristic about it. We then proceeded to take a 3-detector coincidence count in order to look at the g2 number. From here we then took recordings from the B' sensor on the idler beam. This then allowed us to get an ABB' coincidence count. Here we got a value much less than one, which in our case as described above gives us that light has quantum characteristics to it. This then tells us that light is composed of particles and these particles are called photons. This experiment gives us a certainty to the existence of photons but not only that, it expressly shows that of which Thomas Young found in his famous nineteenth century experiment commonly called Young's experiment, which is that light has characteristics of both waves and particles.

Group 3.1: Alex Schachtner, Kevin Masson, Tyler Anderton

Quantum Eraser

Here is where we actually set up the experiment to determine certain characteristics of light, namely the concept of entanglement. We started by placing the interferometer into the signal leg of the system that we had already had in place. We followed the procedure lined up in the Beck book but we still found it to be an incredibly difficult task to align the interferometer correctly. We broke the whole procedure down and found that both the B and B' sensors should be placed on translation stages for easier access. It takes a very large amount of patient in order to setup and odds are since this is on such a small scale that you will have to repeat the procedure many times in order to see any sort of intrference pattern by altering one of the Beam Displacing Prisms (BDPs) and watching the spot get brighter and dimmer as the angle changes. Once properly aligned the alignment laser can be taken out of the setup and then the actual laser diode can be turned on (after lights out procedure) and then you can view the interference pattern that was visually seen now by the photon counts. they should gradually fluctuate such as what is shown below. If properly aligned the B and B' counts should be symmetrical but some issues arose and the interferometer was not competely aligned.

Sadly were not able to get past this part since we had too many complications and so we are now just going to talk theory rather than what we have done experimentally. Here is where we would have placed a polarized into the idler leg and if the system would work properly we would be able to see the photon counts on the B and B'sensors to fluctuate and then this wold show that at certain polarizations of the A sensor the B and B' sensors would be minimum showing the fact that even when the photons are not in contact they are still able to communicate and thus they are constantly entangled, expressly showing the theory of quantum entanglement.

External Resources

Mark Beck's Page, Whitman College

References

1.) Beck, M. Quantum Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2011. Wiley & Sons. [4]

2.) S. P. Walborn, M. O. Terra Cunha, S. Padua, A Double-Slit Quantum Eraser Physical Review A, (65, 033818, 2002).

Original Authors of this page are Alex Schachtner and Kevin Masson. First devised March, 2015.