Difference between revisions of "Mode-locked Erbium-Ytterbium Doped Fiber Laser"

Aplstudent (talk | contribs) (→The Kerr effect) |

Aplstudent (talk | contribs) (→Additive-pulse Mode Locking) |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

The principle used in our fiber laser mode locking are: | The principle used in our fiber laser mode locking are: | ||

| − | - Nonlinear phase shifts in a single-mode fiber. | + | - Nonlinear phase shifts in a single-mode fiber proportional to the intensity of the signal. |

- Pulses returning from the fiber resonator into the main laser resonator interfere with those pulses which already are in the main resonator. | - Pulses returning from the fiber resonator into the main laser resonator interfere with those pulses which already are in the main resonator. | ||

Revision as of 10:18, 17 July 2015

Contents

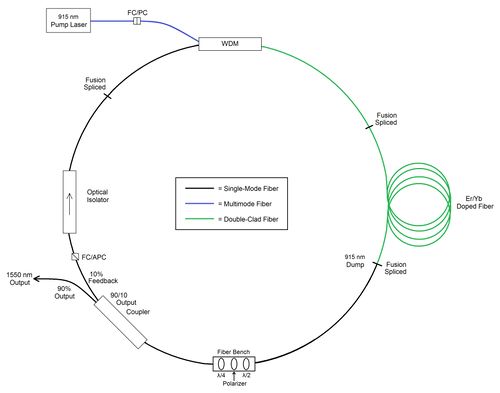

High Power Pulsed Fiber Lasers

Compared to bulk solid-state lasers, the chief advantage of fiber lasers is their outstanding heat-dissipation capability, which is due to the large ratio of surface to volume of such a long, thin gain medium. Fiber lasers and amplifiers have a very high single-pass gain and therefore low laser thresholds and can be efficiently pumped with diode lasers. Moreover, the broad gain bandwidth, the compactness, robustness and simplicity of operation make fiber lasers attractive for a host of applications. Rare-earth-doped PCFs offer several unique properties, which allow an upward scaling of the performance compared to conventional fiber lasers. Their main advantages are the very high pump core NA and an extended possible mode area of truly single-mode cores.

In the pulsed regime, nonlinear processes play a more dominant role and restrict power and energy scaling. However, rare-earth-doped fiber offer features which make them even look promising in this challenging operation regime. The high single-pass gain allows for simple amplification schemes, instead of multi-pass or regenerative amplification, and the average power scalability makes fiber based short-pulse laser systems interesting for applications which ask for high energies in combination with high repetition rates.

Mode Locking

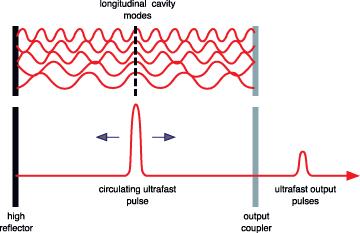

In a simple laser, each of the longitudinal modes oscillates independently, with no fixed relationship between each other, in essence like a set of independent lasers all emitting light at slightly different frequencies. The individual phase of the light waves in each mode is not fixed, and may vary randomly due to such things as thermal changes in materials of the laser. In lasers with only a few oscillating modes, interference between the modes can cause beating effects in the laser output, leading to fluctuations in intensity; in lasers with many thousands of modes, these interference effects tend to average to a near-constant output intensity.

If instead of oscillating independently, each mode operates with a fixed phase between it and the other modes, the laser output behaves quite differently. Instead of a random or constant output intensity, the modes of the laser will periodically all constructively interfere with one another, producing an intense burst or pulse of light. Such a laser is said to be 'mode-locked' or 'phase-locked'. These pulses occur separated in time by τ = 2L/c, where τ is the time taken for the light to make exactly one round trip of the laser cavity. This time corresponds to a frequency exactly equal to the mode spacing of the laser, Δν = 1/τ.

The duration of each pulse of light is determined by the number of modes which are oscillating in phase (in a real laser, it is not necessarily true that all of the laser's modes will be phase-locked). If there are N modes locked with a frequency separation Δν, the overall mode-locked bandwidth is NΔν, and the wider this bandwidth, the shorter the pulse duration from the laser.

Passive Mode Locking

Passive mode-locking techniques are those that do not require a signal external to the laser (such as the driving signal of a modulator) to produce pulses. Rather, they use the light in the cavity to cause a change in some intracavity element, which will then itself produce a change in the intracavity light. A commonly used device to achieve this is a saturable absorber.

A saturable absorber is an optical device that exhibits an intensity-dependent transmission. What this means is that the device behaves differently depending on the intensity of the light passing through it. For passive mode-locking, ideally a saturable absorber will selectively absorb low-intensity light, and transmit light which is of sufficiently high intensity. When placed in a laser cavity, a saturable absorber will attenuate low-intensity constant wave light (pulse wings). However, because of the somewhat random intensity fluctuations experienced by an un-mode-locked laser, any random, intense spike will be transmitted preferentially by the saturable absorber. As the light in the cavity oscillates, this process repeats, leading to the selective amplification of the high-intensity spikes, and the absorption of the low-intensity light. After many round trips, this leads to a train of pulses and mode-locking of the laser.

Additive-pulse Mode Locking

The principle of active mode locking by modulating the resonator losses (AM mode locking) is easy to understand. A pulse with the “correct” timing can pass the modulator at times where the losses are at a minimum. Still, the wings of the pulse experience a little attenuation, which effectively leads to (slight) pulse shortening in each round trip, until this pulse shortening is offset by other effects (e.g. gain narrowing) which tend to broaden the pulse.

For stable operation, the round-trip time of the resonator must fairly precisely match the period of the modulator signal (or some integer multiple of it), so that a circulating pulse can always pass the modulator at a time with minimum losses. Even a small frequency mismatch between the laser resonator and the drive signal can lead to a strong timing jitter or even to chaotic behavior.

Synchronization between the modulator driver and the laser can be achieved either by careful adjustment of a stable laser setup, or by means of a feedback circuit which automatically adjusts either the modulation frequency or the length of the laser resonator.

The principle used in our fiber laser mode locking are:

- Nonlinear phase shifts in a single-mode fiber proportional to the intensity of the signal.

- Pulses returning from the fiber resonator into the main laser resonator interfere with those pulses which already are in the main resonator.

- Constructive interference near the peak of the pulses, but not in the wings, because the latter have acquired different nonlinear phase shifts in the fiber.

- Peak of the circulating pulse is enhanced, whereas the wings are attenuated.

The Kerr effect

This is a passive mode-locking scheme in which nonlinear optical effects in intracavity components are used to provide a method of selectively amplifying high-intensity light in the cavity, and attenuation of low-intensity light.

This uses a nonlinear optical process, the optical Kerr effect, which results in high-intensity light being focussed differently from low-intensity light. By careful arrangement of optics in the laser cavity, this effect can be exploited to produce the equivalent of an ultra-fast response time saturable absorber.

Nonlinear polarization is generated in the medium, which modifies the propagation properties of the light.

The refractive index for the high intensity light beam is modified according to Δn = n' ∙ I (with the nonlinear index n' and the optical intensity I).

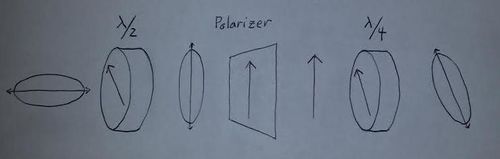

- half wave plate rotates polarization so that the fast axis (highest intensity)is in line with the polarizer;

- the signal passes through polarizer with the narrowing of the pulse due to extinguishing of the low-intensity tail-modes;

- the quarter wave plate turns linearly polarized light into elliptically polarized light so that the non-linear rotation continues:

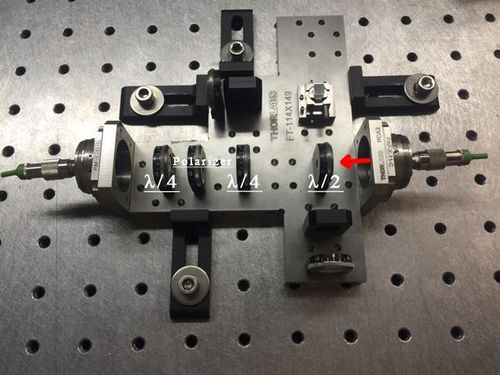

Optical bench showing half wave plate, polarizer, and quarter wave plate; another quarter wave plate has been inserted between half wave plate and polarizer to optimize the maximum intensity signal throughput:

Data

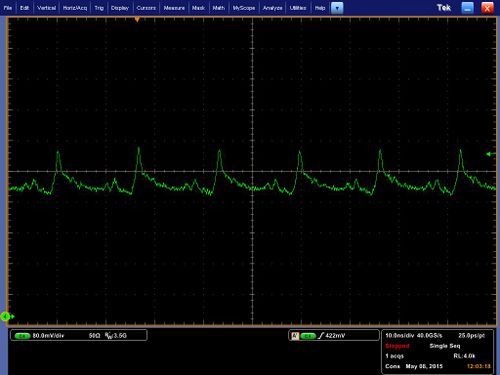

Some initial data: pulses occur one per every round trip time (based on length of all fiber elements), measurement of width of pulses is limited by detector resolution. The noise occurring due to imperfect mode interference is often comparable to the main pulses formed but highly unstable.

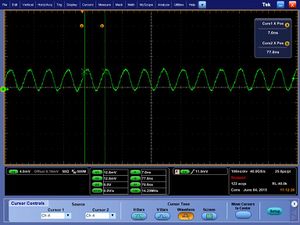

To stabilize the pulses part of the passive fiber was removed and isolator was spliced to the WDM. The pulses became more stable but not as narrow when signal is DC coupled:

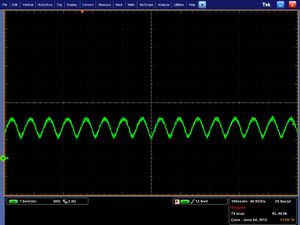

The pulses are seen to be around 10 nanoseconds in width when the signal is AC coupled: